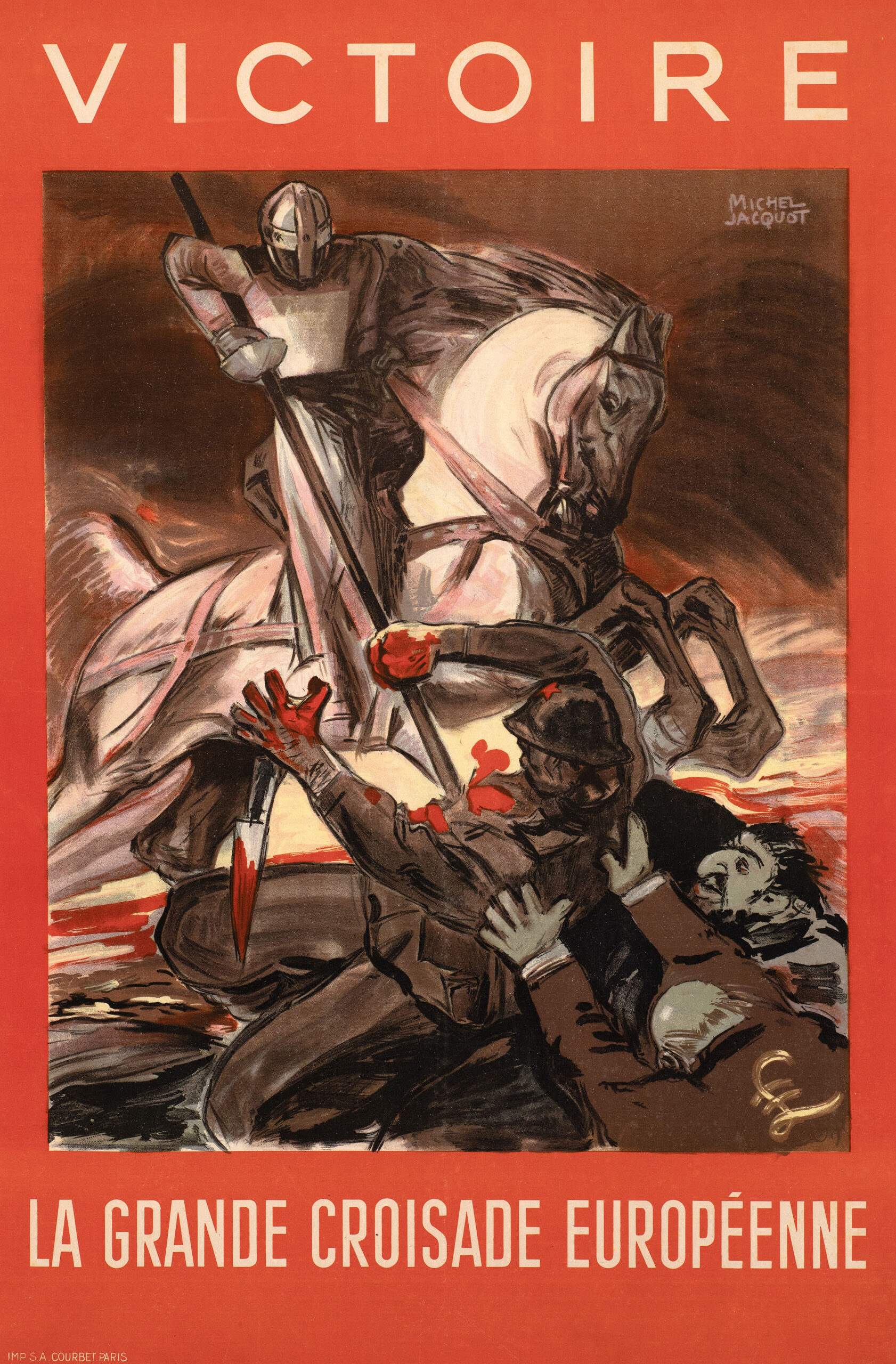

Victory – The Great European Crusade

Propaganda poster from German-occupied France featuring an illustration by Michel Jacquot. Between the text “VICTORY” and “THE GREAT EUROPEAN CRUSADE” rides a valiant European knight impaling a Bolshevik soldier propped up by a Churchill-esque figure. Representing international financial capital, this figure is seen alongside a stereotypical Jewish caricature sharing his efforts, the two collectively symbolizing Judeo-capitalism. Three variations of this red “VICTORY” poster was seen across occupied France, aimed at rallying local support for Germany’s war in the east, euphemistically referred to as the ‘Crusade against Communism’.

Many at the time saw the fight against communism as a patriotic duty that would guarantee the continued existence of their respective nations, as well as Europe as a whole, and saw Germany’s fight in the East as their own. The Germans recognized the immense propaganda value behind this narrative and would call for a ‘Crusade Against Communism’ in the Western European territories they occupied during the war. This war was to be carried out with same divine fervor that inspired the medieval crusades, as a campaign that would define the fate of Christendom and European civilization.

Medieval romanticism and the imagery of knightly warriors are frequent motifs in nationalist aesthetics, as they are thought to embody pre-enlightenment ideals of masculinity, nobility, tradition, duty and martial valor. In doing so, it is the knight that bridges the traditionalist and martial philosophies of the far-right. In fact, the fascist concept of statehood is itself highly feudalistic in its power dynamics due to the two primary aspects of political power, being held on the basis of personal loyalty and guild-based socioeconomics.

The National Socialist doctrine of ‘Blood and Soil’ are reminiscent of feudal property relationships, and the Nazi predilection for Teutonic imagery is well known. Their thinkers found the basis for a Germanic Reich in the medieval notions of Gefolgschaft (comitatus) and Treue (loyalty) as opposed to a Roman legalistic structure or a Byzantine theocratic Machtstaat. Experts on the Germanic origin of feudalism claims that it was the “sound judgement of the Nordic ethos” which rejected the subjugation of creative talents either to dead laws or to autocratic personal authority. The idea of an honorable self, in which subjugation took place by mutual contract, was a principal cultural and political vision for the Germanic Reich. Treue (Loyalty) and Ehre (Honor) were made the ultimate values in life for all upholders of the contract, whether lord or vassal. The Gefolgschaft (comitatus) for the Nazis was the natural political unit and the model for all political relationships. Indeed, the Führerprinzip should be considered a 20th century reinterpretation of feudalism. As in medieval times, the power of a political leader in Nazi Germany was said to be proportional to the confidence and loyalty his voluntary followers. Far from extolling bare force, the Führerprinzip was the rediscovery of the basis of political power: loyalty. And behind that loyalty lay the full and honest acceptance of responsibility by the strong.

National Socialist ideology can thus be classified as being highly feudalistic in nature, condemning the modern state both for its autocratic and its bureaucratic elements. While National Socialism is often criticized for being totalitarian and autocratic itself, one must consider that such measures were exclusive to the last years of the Reich’s existence, while it was undergoing one of the greatest national catastrophes in Germany’s recorded history. It was Marcus Tullius Cicero who stated “The closer the collapse of the Empire, the crazier its laws are.”

Indeed, the National Socialist sympathy for meritocracy and bureaucratic decentralization can be seen in the earliest inspiration for Hitler’s Third Reich, being the highly decentralized First Reich: The Holy Roman Empire. The notion of a Germanic hegemony in Central Europe, over Burgundy, Italy, the Low Countries, Denmark and western Slavdom filled the Führer with a sense of grandeur. It was said Central Europe had only been sufficiently unified by the respect for Germanic cultural traditions that permitted a large-scale political decentralization by means of viceroys and Reichsstatthalter without sacrificing internal stability or flexibility as a larger political unit. Major contingencies would be dealt with by convening a council of such leading men (again invoking medieval images of a ‘council of elders’) while smaller issues would be referred to the local nobility with the guarantee that they would handle matters in the shortest possible order. As seen in practice during the Third Reich, this would mean delegating tasks to subordinates and granting them significant personal autonomy insofar as the mandated task is completed. This is reminiscent of the great Kaisers of old who always retained just enough domains to hold the balance of punitive striking power within the Reich.

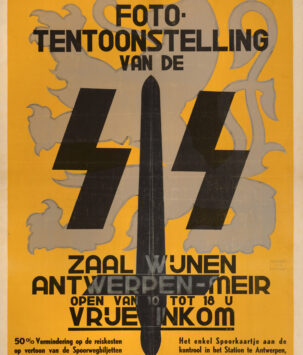

This egalitarian philosophy was also reflected in the ranks of the Schutzstaffel (SS), the bulwark of National Socialism. One of the key differences to every other army at the time was the relationship between officers and their men. Adolf Hitler’s message had always been one of total class unity as opposed to total class war as expressed by the communists. As class prejudice melted away within German society, the same was true within the SS. Officers and men ate together in a manner that would horrify the Americans or British, while total respect was nonetheless paid to those of higher rank. In the barracks, doors and lockers were kept unlocked and a deep sense of communal trust permeated the ranks. Ex-RAF officer and British Union of Fascists member Railton Freedman would go on to join the SS and would comment quote: “the comradeship was terrific, the relationship between officer and man the most democratic I’ve ever known. Yet the discipline was solid as a rock.”

R. W. Darré, the Nazi agrarian, described private property rights as being inherently ‘Roman’. The Germanic idea of property, he claimed, was the right of usufruct and inheritance in return for service rendered to the community, as reflected in the third economic model of fascism known as corporatism, opposed to both communism and capitalism. Darré would speak of a “Germanic aristocracy of the soil”, extending ancient aristocratic conceptions of honor and loyalty to the German peasantry, who were seen as the foundations of the Reich. This would result in a more equitable society for Germans based on merit rather than status. The rough honesty and simplicity of the Teutonic spirit was thus preserved on the land and a “true communalism” was allegedly developed in this class of noble farmers, based on mutuality in service. This spirit was bought out neither by the servility of the West, as seen in the status of a Frankish serf, nor the destruction of individuality by the Slavic village community. It is again appropriate to note the historical trajectory that all three regions would take in its economic policy thereafter with capitalism spawning in the west, communism in the east and corporatist fascism across historically feudal Europe and Japan.

Regardless of historical validity, Darré’s account serves as a clearcut analogy for the corporatist economic model adopted by Germany and her fascist allies including Italy and Japan. Contrary to popular belief, corporatism does not refer to a political system dominated by large business interests, even though the latter are commonly referred to as ‘corporations’ in modern American vernacular. Instead, Germanic National Socialism as well as fascist economics more broadly encourages competition alongside land management responsible to the wider community, brilliant synthesis of pragmatism with ethics.

Darré would continue that “this limited freedom in the use of land was the price paid by the Germans; when modern Germans refused to pay it because of the reforms of the French Revolution, German property relationships became chaotic.” According to Darré, the first task of National Socialism, was thus to free the German peasant from “the chaos of a market economy.”

German farmers were first freed from any past debts and would receive hereditary land as estates from the Reich. These farmers were all then required to take part in a cooperative marketing network to resist external market forces as an economic appendage of the Reich representing its agricultural sector. Named the Reichsnährstand, it was much more than a compulsory marketing organization, however, and was intended by Darré to be a corporative estate of food producers. Darré meant it to be an autonomous, self-governing unit of a pluralistic future German society. Through its power, vis-à-vis the individual peasant, and vis-à-vis German society, he hoped it would pave the way for a new aristocracy of “Blood and Soil”.

There were also calls to nationalize German industry to then be parceled out as fiefs to the managers and tycoons who had built them. Each economic sector was to be run like a medieval guild, with a regular provision for advancement to managerial status for those who prove proficient, and strict internal controls on competition and production. The National Socialists wished to do away with Prussia and with the Reichstag, substituting it with an economic-regional federalism and a chamber of corporations.

The final item on the theme of Nazi medievalism, while not explicitly feudal, is composed of several elements linked to it. National Socialist historians, as well as Rosenberg and Himmler, venerated the Teutonic Order. For them the essence of the Order was in its elitism, as they too considered themselves an elaboration of the warband, a self-constituted league of fighting aristocrats. However, only the dedicated were able to sustain the pitiless self-subordination to the higher purposes of the Order. It was in the Teutonic Order that the Hegelian synthesis of Germanic pride and Christian humility was fused to create Prussiandom. The Ordensritter (order-knight) was a knight sans peur sans reproche, not for himself, not for Holy Church, but for an Idea. That this Idea was not fully revealed to him, though concerned somehow with the future and with Europe as a whole, was an advantage, not a drawback. Quite consciously did Rosenberg call upon the NSDAP to make itself the German Order of the 20th century in the service of the ‘unknown God’. Similarly, Himmler devised his elite guard the Schutzstaffel (SS) in a conscious effort to form a new pioneering nobility for a future Germanic conquest of the east. This conquest, too, was inspired by the eastern expansion of Germans during the Middle Ages known as the Ostsiedlung. As the vanguard force reviving this Germanic ‘manifest destiny’, Himmler tried to instill in the SS a natural piety and reverential disposition toward the creative forces of nature, while their motto Meine Ehre heißt Treue (my honor is loyalty) again harks back to the dualistic primacy that the notions of honor and loyalty held.

Despite a certain pretentiousness, within the National Socialist talk of “man-to-man loyalty” and the “Führer’s steadfast followers” was a genuine expression of their deepest convictions. This is revealed in both the formal systems they created to run Germany and in the informal structure of their internal politics. It is sometimes said that National Socialism lacked a real ideology. Insofar as a rational and systematic philosophy is meant, this is true. Yet no elaborate semantics are needed to find consistency in the Nazi Weltanschauung (worldview), for above all, they believed in a modern version of an elective kingship. The Führer was in reality chosen and maintained power through his ‘paladins’ who chose him for his personal qualities. These paladins, such as Heinrich Himmler, would in turn be permitted to rule their individual ‘fiefdoms’ with great autonomy, insofar as they carry out the Führer’s will. Indeed, Himmler’s SS was often described as a “state within a state”, reflecting this tenet of organic autonomy.

It is said that the National Socialists, in fact, attempted to deliberately de-program the instinctive loyalty Germans had to abstract law and order, and to the state and to tradition. They instead instituted an oath of personal loyalty to the Führer Adolf Hitler and sanctioned an abundant series of subinfeudations via oaths extorted by the so-called ‘little Führers‘. In legislation, jurisprudence, police practice and administrative policy, men were substituted for laws, personal judgment and responsibility, with this power in turn being enabled only through the faith of one’s subordinates.

Free shipping on orders over $50!

- Satisfaction Guaranteed

- No Hassle Refunds

- Secure Payments

Propaganda poster from German-occupied France featuring an illustration by Michel Jacquot. Between the text “VICTORY” and “THE GREAT EUROPEAN CRUSADE” rides a valiant European knight impaling a Bolshevik soldier propped up by a Churchill-esque figure. Representing international financial capital, this figure is seen alongside a stereotypical Jewish caricature sharing his efforts, the two collectively symbolizing Judeo-capitalism. Three variations of this red “VICTORY” poster was seen across occupied France, aimed at rallying local support for Germany’s war in the east, euphemistically referred to as the ‘Crusade against Communism’.

Many at the time saw the fight against communism as a patriotic duty that would guarantee the continued existence of their respective nations, as well as Europe as a whole, and saw Germany’s fight in the East as their own. The Germans recognized the immense propaganda value behind this narrative and would call for a ‘Crusade Against Communism’ in the Western European territories they occupied during the war. This war was to be carried out with same divine fervor that inspired the medieval crusades, as a campaign that would define the fate of Christendom and European civilization.

Medieval romanticism and the imagery of knightly warriors are frequent motifs in nationalist aesthetics, as they are thought to embody pre-enlightenment ideals of masculinity, nobility, tradition, duty and martial valor. In doing so, it is the knight that bridges the traditionalist and martial philosophies of the far-right. In fact, the fascist concept of statehood is itself highly feudalistic in its power dynamics due to the two primary aspects of political power, being held on the basis of personal loyalty and guild-based socioeconomics.

The National Socialist doctrine of ‘Blood and Soil’ are reminiscent of feudal property relationships, and the Nazi predilection for Teutonic imagery is well known. Their thinkers found the basis for a Germanic Reich in the medieval notions of Gefolgschaft (comitatus) and Treue (loyalty) as opposed to a Roman legalistic structure or a Byzantine theocratic Machtstaat. Experts on the Germanic origin of feudalism claims that it was the “sound judgement of the Nordic ethos” which rejected the subjugation of creative talents either to dead laws or to autocratic personal authority. The idea of an honorable self, in which subjugation took place by mutual contract, was a principal cultural and political vision for the Germanic Reich. Treue (Loyalty) and Ehre (Honor) were made the ultimate values in life for all upholders of the contract, whether lord or vassal. The Gefolgschaft (comitatus) for the Nazis was the natural political unit and the model for all political relationships. Indeed, the Führerprinzip should be considered a 20th century reinterpretation of feudalism. As in medieval times, the power of a political leader in Nazi Germany was said to be proportional to the confidence and loyalty his voluntary followers. Far from extolling bare force, the Führerprinzip was the rediscovery of the basis of political power: loyalty. And behind that loyalty lay the full and honest acceptance of responsibility by the strong.

National Socialist ideology can thus be classified as being highly feudalistic in nature, condemning the modern state both for its autocratic and its bureaucratic elements. While National Socialism is often criticized for being totalitarian and autocratic itself, one must consider that such measures were exclusive to the last years of the Reich’s existence, while it was undergoing one of the greatest national catastrophes in Germany’s recorded history. It was Marcus Tullius Cicero who stated “The closer the collapse of the Empire, the crazier its laws are.”

Indeed, the National Socialist sympathy for meritocracy and bureaucratic decentralization can be seen in the earliest inspiration for Hitler’s Third Reich, being the highly decentralized First Reich: The Holy Roman Empire. The notion of a Germanic hegemony in Central Europe, over Burgundy, Italy, the Low Countries, Denmark and western Slavdom filled the Führer with a sense of grandeur. It was said Central Europe had only been sufficiently unified by the respect for Germanic cultural traditions that permitted a large-scale political decentralization by means of viceroys and Reichsstatthalter without sacrificing internal stability or flexibility as a larger political unit. Major contingencies would be dealt with by convening a council of such leading men (again invoking medieval images of a ‘council of elders’) while smaller issues would be referred to the local nobility with the guarantee that they would handle matters in the shortest possible order. As seen in practice during the Third Reich, this would mean delegating tasks to subordinates and granting them significant personal autonomy insofar as the mandated task is completed. This is reminiscent of the great Kaisers of old who always retained just enough domains to hold the balance of punitive striking power within the Reich.

This egalitarian philosophy was also reflected in the ranks of the Schutzstaffel (SS), the bulwark of National Socialism. One of the key differences to every other army at the time was the relationship between officers and their men. Adolf Hitler’s message had always been one of total class unity as opposed to total class war as expressed by the communists. As class prejudice melted away within German society, the same was true within the SS. Officers and men ate together in a manner that would horrify the Americans or British, while total respect was nonetheless paid to those of higher rank. In the barracks, doors and lockers were kept unlocked and a deep sense of communal trust permeated the ranks. Ex-RAF officer and British Union of Fascists member Railton Freedman would go on to join the SS and would comment quote: “the comradeship was terrific, the relationship between officer and man the most democratic I’ve ever known. Yet the discipline was solid as a rock.”

R. W. Darré, the Nazi agrarian, described private property rights as being inherently ‘Roman’. The Germanic idea of property, he claimed, was the right of usufruct and inheritance in return for service rendered to the community, as reflected in the third economic model of fascism known as corporatism, opposed to both communism and capitalism. Darré would speak of a “Germanic aristocracy of the soil”, extending ancient aristocratic conceptions of honor and loyalty to the German peasantry, who were seen as the foundations of the Reich. This would result in a more equitable society for Germans based on merit rather than status. The rough honesty and simplicity of the Teutonic spirit was thus preserved on the land and a “true communalism” was allegedly developed in this class of noble farmers, based on mutuality in service. This spirit was bought out neither by the servility of the West, as seen in the status of a Frankish serf, nor the destruction of individuality by the Slavic village community. It is again appropriate to note the historical trajectory that all three regions would take in its economic policy thereafter with capitalism spawning in the west, communism in the east and corporatist fascism across historically feudal Europe and Japan.

Regardless of historical validity, Darré’s account serves as a clearcut analogy for the corporatist economic model adopted by Germany and her fascist allies including Italy and Japan. Contrary to popular belief, corporatism does not refer to a political system dominated by large business interests, even though the latter are commonly referred to as ‘corporations’ in modern American vernacular. Instead, Germanic National Socialism as well as fascist economics more broadly encourages competition alongside land management responsible to the wider community, brilliant synthesis of pragmatism with ethics.

Darré would continue that “this limited freedom in the use of land was the price paid by the Germans; when modern Germans refused to pay it because of the reforms of the French Revolution, German property relationships became chaotic.” According to Darré, the first task of National Socialism, was thus to free the German peasant from “the chaos of a market economy.”

German farmers were first freed from any past debts and would receive hereditary land as estates from the Reich. These farmers were all then required to take part in a cooperative marketing network to resist external market forces as an economic appendage of the Reich representing its agricultural sector. Named the Reichsnährstand, it was much more than a compulsory marketing organization, however, and was intended by Darré to be a corporative estate of food producers. Darré meant it to be an autonomous, self-governing unit of a pluralistic future German society. Through its power, vis-à-vis the individual peasant, and vis-à-vis German society, he hoped it would pave the way for a new aristocracy of “Blood and Soil”.

There were also calls to nationalize German industry to then be parceled out as fiefs to the managers and tycoons who had built them. Each economic sector was to be run like a medieval guild, with a regular provision for advancement to managerial status for those who prove proficient, and strict internal controls on competition and production. The National Socialists wished to do away with Prussia and with the Reichstag, substituting it with an economic-regional federalism and a chamber of corporations.

The final item on the theme of Nazi medievalism, while not explicitly feudal, is composed of several elements linked to it. National Socialist historians, as well as Rosenberg and Himmler, venerated the Teutonic Order. For them the essence of the Order was in its elitism, as they too considered themselves an elaboration of the warband, a self-constituted league of fighting aristocrats. However, only the dedicated were able to sustain the pitiless self-subordination to the higher purposes of the Order. It was in the Teutonic Order that the Hegelian synthesis of Germanic pride and Christian humility was fused to create Prussiandom. The Ordensritter (order-knight) was a knight sans peur sans reproche, not for himself, not for Holy Church, but for an Idea. That this Idea was not fully revealed to him, though concerned somehow with the future and with Europe as a whole, was an advantage, not a drawback. Quite consciously did Rosenberg call upon the NSDAP to make itself the German Order of the 20th century in the service of the ‘unknown God’. Similarly, Himmler devised his elite guard the Schutzstaffel (SS) in a conscious effort to form a new pioneering nobility for a future Germanic conquest of the east. This conquest, too, was inspired by the eastern expansion of Germans during the Middle Ages known as the Ostsiedlung. As the vanguard force reviving this Germanic ‘manifest destiny’, Himmler tried to instill in the SS a natural piety and reverential disposition toward the creative forces of nature, while their motto Meine Ehre heißt Treue (my honor is loyalty) again harks back to the dualistic primacy that the notions of honor and loyalty held.

Despite a certain pretentiousness, within the National Socialist talk of “man-to-man loyalty” and the “Führer’s steadfast followers” was a genuine expression of their deepest convictions. This is revealed in both the formal systems they created to run Germany and in the informal structure of their internal politics. It is sometimes said that National Socialism lacked a real ideology. Insofar as a rational and systematic philosophy is meant, this is true. Yet no elaborate semantics are needed to find consistency in the Nazi Weltanschauung (worldview), for above all, they believed in a modern version of an elective kingship. The Führer was in reality chosen and maintained power through his ‘paladins’ who chose him for his personal qualities. These paladins, such as Heinrich Himmler, would in turn be permitted to rule their individual ‘fiefdoms’ with great autonomy, insofar as they carry out the Führer’s will. Indeed, Himmler’s SS was often described as a “state within a state”, reflecting this tenet of organic autonomy.

It is said that the National Socialists, in fact, attempted to deliberately de-program the instinctive loyalty Germans had to abstract law and order, and to the state and to tradition. They instead instituted an oath of personal loyalty to the Führer Adolf Hitler and sanctioned an abundant series of subinfeudations via oaths extorted by the so-called ‘little Führers‘. In legislation, jurisprudence, police practice and administrative policy, men were substituted for laws, personal judgment and responsibility, with this power in turn being enabled only through the faith of one’s subordinates.