Edo Sword

One of the most unique images from the Second World War is that of the katana being carried into battle by Imperial Japanese servicemen, juxtaposed alongside various other modern arms of war. These swords were not only weapons but precious works of art, holding great spiritual significance within the indigenous Japanese religion of Shinto. Akin to the beliefs of Germanic Paganism embraced by the Nazis, it is held within Shinto that every physical object is imbued with a certain divine essence. The katana is thus believed to be capable of imbuing its user with its martial essence held within. The katana’s sense of mystery, violence and conquest would be embraced as both a metaphor and a tool for Shinto practitioners within Imperial Japan, and form part of the nation’s quasi-religious military precepts.

Pictured herein is one such sword, a bona fide katana from the Edo period (1603-1867) mounted on Second World War army fittings. Adorned on the pommel is the crest of the Takeda clan, an ancient samurai lineage which rose to prominence under Takeda Shingen, the “Tiger of Kai”, during the Sengoku period (1477-1573).

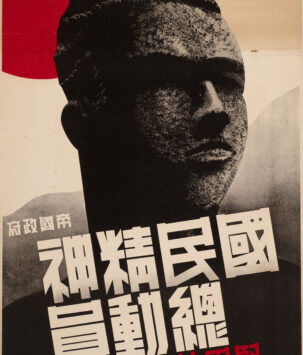

Nationalism looks to the past to advise current realities, and Japanese militarists were no different in taking inspiration from the venerable samurai warriors of yore, their revered martial tradition embodied by the katana as seen here. In response to rising nationalist sentiment within the armed forces, a new style of sword was designed for the Japanese military styled after a traditional tachi of the Kamakura Period (1185–1332). By the late 1930s, the rise of militarism in Japan created at least superficial similarities between the wider Japanese military culture and that of Nazi Germany’s elite military personnel, such as that of the Waffen-SS.

Japanese soldiers during the Second World War garnered a reputation for their ferocity and unrelenting spirit in the face of countless unfavorable engagements. This was undoubtedly due to Japan’s military culture which placed a heavy emphasis on morale. The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), despite being a modern military force, was founded on the feudal concept of Bushido (the way of the warrior), the moral code of the ancient samurai in which honor surmounted all else. In order to instill this warrior spirit in their soldiers and cement their ancestral link to the fearsome warriors of yore, the Japanese High Command endowed all officers with a traditional Japanese katana, just as their exalted samurai ancestors would have held. However anachronistic or impractical a medieval sword may be in modern combat, its effect on troop morale was undeniable. Believing war to be purifying and death in combat an honorable duty, Japanese soldiers during the Second Sino-Japanese War mounted valiant arme blanche charges which often routed their undisciplined Chinese adversaries but resulted in mass casualties when facing off against automatic American weapons.

This seldom discouraged such suicidal tactics, as death in service of the emperor, being viewed by the Japanese as their honor-bound duty, was not only exhorted but actively pursued with enthusiasm and as part of official Japanese military doctrine. This resulted in the exceptionally few number of Japanese soldiers taken prisoner by the Allies as many chose death over dishonor. While over 1.5 million German soldiers surrendered to the Allies in Europe during the final weeks of the Second World War, not a single record of an organized unit of the IJA surrendering over the course of the entire conflict – an unprecedented incidence in the annals of modern warfare. These views are crystallized in the great 17th century classic of Bushido, Hagakure: “Bushido is realized in the presence of death. This means choosing death whenever there is a choice between life and death. There is no other reasoning.”

Written by the samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo, Hagakure came to be viewed as the definitive spiritual guide for the Imperial armed forces. While the quote is often misconstrued as encouraging the reckless pursuit of death for death’s sake, its true meaning is that by living as though one was already dead and having a constant awareness of death, people can achieve a transcendent state of freedom wherein it is possible to perfectly fulfill one’s calling as a warrior. Psychologically, this satisfied the innate human need for transcendence of the individual self, turning every soldier into a living vessel of tradition and national destiny. It is within this context that Bushido asserts that a samurai must be willing to die at any moment in order to be true to his sovereign. It is akin to the notion that only through acknowledging the fragility of life can we come to fully appreciate its majesty. Hagakure presents a mystical beauty intrinsic to the Japanese aesthetic experience; a stoic and profound appreciation of the meaning of life and death. This spiritually grounded and purposeful mode of thinking permeated the Japanese psyche for eons until its spiritual desecration at the hands of the Americans in 1945.

The cherry blossom, visible on the menuki of the sword’s grip, is yet another enduring metaphor in Japanese culture for the ephemeral beauty of life, referencing the spectacle of their blooming and falling en masse all within the mere span of a week. The lyrics of a famous military composition compares cherry blossoms to the destiny of Japan’s soldiers: “Flowers only bloom being prepared to fall, so let us scatter like cherry blossoms in the wind, for the sake of our nation.”

For all its profound teachings on the ephemerality of life, Bushido also helps explain the ruthless conduct of the Imperial forces and their numerous, well-documented and brutal war crimes. The Japanese frequently employed these dreaded katanas to behead captured Allied prisoners of war (POWs) and civilians alike. Having its roots in samurai culture, the practice of beheading captured soldiers, far from being an act of cruelty, was considered a show of mercy and respect towards the vanquished to spare them the dishonor of defeat. The IJA thus claimed, in a bizarre twist of logic, that the POWs they executed were treated generously by virtue of Bushido principles.

At times, because of one man’s evil, ten thousand people suffer. So you kill that one man to let the tens of thousands live. Here truly the blade that deals death becomes the sword that saves. — Yamamoto Tsunetomo, Hagakure

Free shipping on orders over $50!

- Satisfaction Guaranteed

- No Hassle Refunds

- Secure Payments

One of the most unique images from the Second World War is that of the katana being carried into battle by Imperial Japanese servicemen, juxtaposed alongside various other modern arms of war. These swords were not only weapons but precious works of art, holding great spiritual significance within the indigenous Japanese religion of Shinto. Akin to the beliefs of Germanic Paganism embraced by the Nazis, it is held within Shinto that every physical object is imbued with a certain divine essence. The katana is thus believed to be capable of imbuing its user with its martial essence held within. The katana’s sense of mystery, violence and conquest would be embraced as both a metaphor and a tool for Shinto practitioners within Imperial Japan, and form part of the nation’s quasi-religious military precepts.

Pictured herein is one such sword, a bona fide katana from the Edo period (1603-1867) mounted on Second World War army fittings. Adorned on the pommel is the crest of the Takeda clan, an ancient samurai lineage which rose to prominence under Takeda Shingen, the “Tiger of Kai”, during the Sengoku period (1477-1573).

Nationalism looks to the past to advise current realities, and Japanese militarists were no different in taking inspiration from the venerable samurai warriors of yore, their revered martial tradition embodied by the katana as seen here. In response to rising nationalist sentiment within the armed forces, a new style of sword was designed for the Japanese military styled after a traditional tachi of the Kamakura Period (1185–1332). By the late 1930s, the rise of militarism in Japan created at least superficial similarities between the wider Japanese military culture and that of Nazi Germany’s elite military personnel, such as that of the Waffen-SS.

Japanese soldiers during the Second World War garnered a reputation for their ferocity and unrelenting spirit in the face of countless unfavorable engagements. This was undoubtedly due to Japan’s military culture which placed a heavy emphasis on morale. The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), despite being a modern military force, was founded on the feudal concept of Bushido (the way of the warrior), the moral code of the ancient samurai in which honor surmounted all else. In order to instill this warrior spirit in their soldiers and cement their ancestral link to the fearsome warriors of yore, the Japanese High Command endowed all officers with a traditional Japanese katana, just as their exalted samurai ancestors would have held. However anachronistic or impractical a medieval sword may be in modern combat, its effect on troop morale was undeniable. Believing war to be purifying and death in combat an honorable duty, Japanese soldiers during the Second Sino-Japanese War mounted valiant arme blanche charges which often routed their undisciplined Chinese adversaries but resulted in mass casualties when facing off against automatic American weapons.

This seldom discouraged such suicidal tactics, as death in service of the emperor, being viewed by the Japanese as their honor-bound duty, was not only exhorted but actively pursued with enthusiasm and as part of official Japanese military doctrine. This resulted in the exceptionally few number of Japanese soldiers taken prisoner by the Allies as many chose death over dishonor. While over 1.5 million German soldiers surrendered to the Allies in Europe during the final weeks of the Second World War, not a single record of an organized unit of the IJA surrendering over the course of the entire conflict – an unprecedented incidence in the annals of modern warfare. These views are crystallized in the great 17th century classic of Bushido, Hagakure: “Bushido is realized in the presence of death. This means choosing death whenever there is a choice between life and death. There is no other reasoning.”

Written by the samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo, Hagakure came to be viewed as the definitive spiritual guide for the Imperial armed forces. While the quote is often misconstrued as encouraging the reckless pursuit of death for death’s sake, its true meaning is that by living as though one was already dead and having a constant awareness of death, people can achieve a transcendent state of freedom wherein it is possible to perfectly fulfill one’s calling as a warrior. Psychologically, this satisfied the innate human need for transcendence of the individual self, turning every soldier into a living vessel of tradition and national destiny. It is within this context that Bushido asserts that a samurai must be willing to die at any moment in order to be true to his sovereign. It is akin to the notion that only through acknowledging the fragility of life can we come to fully appreciate its majesty. Hagakure presents a mystical beauty intrinsic to the Japanese aesthetic experience; a stoic and profound appreciation of the meaning of life and death. This spiritually grounded and purposeful mode of thinking permeated the Japanese psyche for eons until its spiritual desecration at the hands of the Americans in 1945.

The cherry blossom, visible on the menuki of the sword’s grip, is yet another enduring metaphor in Japanese culture for the ephemeral beauty of life, referencing the spectacle of their blooming and falling en masse all within the mere span of a week. The lyrics of a famous military composition compares cherry blossoms to the destiny of Japan’s soldiers: “Flowers only bloom being prepared to fall, so let us scatter like cherry blossoms in the wind, for the sake of our nation.”

For all its profound teachings on the ephemerality of life, Bushido also helps explain the ruthless conduct of the Imperial forces and their numerous, well-documented and brutal war crimes. The Japanese frequently employed these dreaded katanas to behead captured Allied prisoners of war (POWs) and civilians alike. Having its roots in samurai culture, the practice of beheading captured soldiers, far from being an act of cruelty, was considered a show of mercy and respect towards the vanquished to spare them the dishonor of defeat. The IJA thus claimed, in a bizarre twist of logic, that the POWs they executed were treated generously by virtue of Bushido principles.

At times, because of one man’s evil, ten thousand people suffer. So you kill that one man to let the tens of thousands live. Here truly the blade that deals death becomes the sword that saves. — Yamamoto Tsunetomo, Hagakure