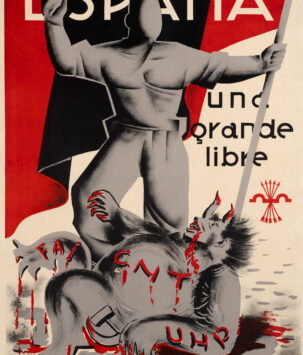

The Walloon Legion – Join Us!

Poster from occupied Belgium recruiting for the Walloon Legion, later designated the SS-Sturmbrigade Wallonien (SS Assault Brigade Wallonia) and before being reorganized again as the SS-Freiwilligen-Grenadier-Division Wallonien (SS Volunteer Grenadier Division Wallonia).

The unit was raised in 1941 by the then head of the Rexist Party, Leon Degrelle, who would distinguish himself through repeated and remarkable feats of bravery on the Eastern Front as the unit’s commander. Upon hearing about the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Degrelle would declare his unconditional support for the attack. He would offer to to raise a volunteer battalion of his fellow French-speaking Walloons to join the fight against Bolshevism, convinced this would ensure Belgium a place of honor in Hitler’s coming ‘new order’ for Europe. The unit, christened the Légion Wallonie (Walloon Legion), would see heavy frontline action on the Eastern Front and fight alongside their German comrades till the bitter end.

Initially, the Walloon Legion would be assigned to rearguard anti-partisan (Bandenbekämpfung) duties by the Germans who were skeptical of the combat prowess of these untried volunteers. The Slavic guerrillas with whom they were engaged adhered to no set order of battle order or military doctrine, and the irregular hit-and-run tactics they employed were difficult to counter or anticipate. The inexperienced legionnaires were thrown into an extraordinarily cruel type of warfare that often required them to kill quasi-civilians whom were impossible to distinguish from the terrorists they harbored and whom would hide amongst women and children. These anti-partisan duties, characterized by a ruthless barbarity considered too grizzly for military journalists to report, was not the war the Belgians had envisaged or signed up for. The sobering fact was that there were no glorious battles, just endless, terrifying skirmishes through the forests, swamps and subzero temperatures of the vast Russian wilderness. Exposure to the terrifying brutalities of the front line with all its sickening horror, death, and sorrow had shaken the Belgians to the core.

The Walloons experienced their first taste of frontline combat against the Soviet forces beginning in 1942, where against overwhelming Russian forces, the heavily outnumbered legion showed remarkable combat prowess, courage and grim determination fighting alongside Waffen-SS troops. Among those decorated was Degrelle himself, who was awarded the Iron Cross for his bravery and inspirational leadership during savage hand-to-hand combat. This baptism of fire against Red Army troops came at a horrendous cost for the Legion. A third of its men and almost all of its officers had been killed or wounded. Despite the grievous losses, the fighting qualities and astonishing tenacity displayed by the Belgians finally earned them the admiration and respect of Wehrmacht troops. With the Walloons’ reputation greatly enhanced, the thawing of relations with their German counterparts restored flagging morale, as did their considerable successes in the savage battles that awaited them during the autumn of 1942.

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler considered the now battle-proven Walloons worthy of admission into his personal elite paramilitary, and the unit was reorganized as the 5th SS-Freiwilligen-Sturmbrigade Wallonien with SS-Hauptstürmfuhrer (Captain) Leon Degrelle as its chief of staff. Elevated to new heights of combat prowess, the 2,000 men of the now fully motorized brigade were rushed to the Ukranian sector of the front in November 1943 to halt the Russian advance. During the bloody engagement, the brigade commander was killed, and it fell to Degrelle to quickly take command of what was left of the shattered unit. Degrelle’s questionable grasp of military strategy was compensated for by his unflinching courage, cool head and hard-won battle experience. At a time when the fate of the Walloons hung by a thread, it was often Degrelle’s qualities as a fighting leader that set the example for his men. Few of his troops would ever forget seeing Degrelle, in agony from a deep wound in his side, continue to personally lead them through fighting so ghastly that it was considered completely beyond the comprehension of anyone who had not lived through it.

Despite the hellish conditions, the Belgians managed to hold back the Russian onslaught. Dragging their wounded with them, they fought alongside German units in a desperate rear-guard action through lethal Russian rocket and artillery fire. However, as Degrelle and the exhausted remnants of the brigade closed on the German lines, they appeared certain to be overtaken and massacred by the pursuing Russians. In a heroic act of self-sacrifice, the 5th SS-Panzerdivision Wiking‘s few remaining panzers suddenly turned back to hold off the Red Army units until the Belgians had reached safety.

The heroic stand came at a heavy cost to the brigade but Degrelle would be promoted to SS-Sturmbannführer (Major) and flown out of Russia to be awarded the Knight’s Cross personally by Hitler for his incredible bravery. As the two men discussed the situation on the front, it was apparent that Hitler not only had a great personal interest in the progress of the brigade but also held Degrelle in high esteem.

In 1944, the brigade found themselves almost encircled in the Baltic, fending off an insurmountable onslaught. For three weeks during the Battle of Narva, Degrelle’s mostly inexperienced Walloons had been committed to heavy combat. Only 32 of the original 300 recruits survived to rejoin the unit. Degrelle was flown out of Estonia and once again brought before Hitler on August 27, 1944. He had the unique distinction of being one of the few non-ethnic Germans to be awarded the coveted Oak Leaves to the Knights Cross along with the prestigious Close Combat Clasp in gold, awarded to men who had fought through more than 50 days of close-quarter combat. During this encounter, Hitler is said to have stated to Degrelle that “If I had a son, I would want him to be like you”.

Despite being virtually annihilated during its service in Russia and Estonia, the Wallonien Brigade was to be upgraded in September 1944 to form the 28th SS-Division, commanded by the now SS-Oberstürmbannfuhrer (Lieutenant Colonel) Leon Degrelle.

In the waning months of the Reich, an offensive in Pomerania was launched with all the customary élan and ferocity typical of the Waffen-SS. Degrelle once again led from the front as his Walloons fought fanatically in the face of overpowering Soviet forces. The offensive soon stalled however, and ultimately accomplished little other than to precipitate a powerful Soviet counteroffensive. They were doggedly forced back through central Pomerania and towards Berlin. By mid-March 1945, following weeks of unrelenting combat in the hopelessly one-sided fight, Degrelle’s division had been burned to a cinder.

As destruction loomed at the gates of the German capital, Degrelle saw ample evidence of the German Army’s total collapse. The stiff, lifeless bodies of countless Wehrmacht and Volkssturm soldiers, suspected of desertion, had been left hanging by the roadside from trees, lamp posts, and makeshift gallows as a gruesome warning to others. In spite of the draconian measures being employed by the SS, Degrelle decided to release those volunteers who no longer wished to fight. They were free to make their way home to Belgium or elsewhere. Others were given foreign worker cards and disguised as conscripted laborers. From the remaining 650 officers and men, he formed one well-equipped battalion to continue the futile struggle. Even though Hitler was dead, the remaining Walloons recognized that as foreign volunteers they had no future beyond the Reich and would be treated as traitors in their homeland despite their unimaginable sacrifice. Their fate was sealed. With the sword of Damocles hanging over their heads, many saw death in combat as the only course open to them, and were determined to fight to the bitter end.

“They died out there, in countless numbers, not for government officials in Berlin, but for their old countries, gilded by the centuries, and for their common fatherland, Europe, the Europe of Virgil and Ronsard, the Europe of Erasmus and Nietzsche, of Raphael and Dürer, the Europe of St. Ignatius and St. Theresa, the Europe of Frederick the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte.” — Leon Degrelle, The Eastern Front: Memoirs of a Waffen SS Volunteer, 1941–1945

Free shipping on orders over $50!

- Satisfaction Guaranteed

- No Hassle Refunds

- Secure Payments

Poster from occupied Belgium recruiting for the Walloon Legion, later designated the SS-Sturmbrigade Wallonien (SS Assault Brigade Wallonia) and before being reorganized again as the SS-Freiwilligen-Grenadier-Division Wallonien (SS Volunteer Grenadier Division Wallonia).

The unit was raised in 1941 by the then head of the Rexist Party, Leon Degrelle, who would distinguish himself through repeated and remarkable feats of bravery on the Eastern Front as the unit’s commander. Upon hearing about the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Degrelle would declare his unconditional support for the attack. He would offer to to raise a volunteer battalion of his fellow French-speaking Walloons to join the fight against Bolshevism, convinced this would ensure Belgium a place of honor in Hitler’s coming ‘new order’ for Europe. The unit, christened the Légion Wallonie (Walloon Legion), would see heavy frontline action on the Eastern Front and fight alongside their German comrades till the bitter end.

Initially, the Walloon Legion would be assigned to rearguard anti-partisan (Bandenbekämpfung) duties by the Germans who were skeptical of the combat prowess of these untried volunteers. The Slavic guerrillas with whom they were engaged adhered to no set order of battle order or military doctrine, and the irregular hit-and-run tactics they employed were difficult to counter or anticipate. The inexperienced legionnaires were thrown into an extraordinarily cruel type of warfare that often required them to kill quasi-civilians whom were impossible to distinguish from the terrorists they harbored and whom would hide amongst women and children. These anti-partisan duties, characterized by a ruthless barbarity considered too grizzly for military journalists to report, was not the war the Belgians had envisaged or signed up for. The sobering fact was that there were no glorious battles, just endless, terrifying skirmishes through the forests, swamps and subzero temperatures of the vast Russian wilderness. Exposure to the terrifying brutalities of the front line with all its sickening horror, death, and sorrow had shaken the Belgians to the core.

The Walloons experienced their first taste of frontline combat against the Soviet forces beginning in 1942, where against overwhelming Russian forces, the heavily outnumbered legion showed remarkable combat prowess, courage and grim determination fighting alongside Waffen-SS troops. Among those decorated was Degrelle himself, who was awarded the Iron Cross for his bravery and inspirational leadership during savage hand-to-hand combat. This baptism of fire against Red Army troops came at a horrendous cost for the Legion. A third of its men and almost all of its officers had been killed or wounded. Despite the grievous losses, the fighting qualities and astonishing tenacity displayed by the Belgians finally earned them the admiration and respect of Wehrmacht troops. With the Walloons’ reputation greatly enhanced, the thawing of relations with their German counterparts restored flagging morale, as did their considerable successes in the savage battles that awaited them during the autumn of 1942.

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler considered the now battle-proven Walloons worthy of admission into his personal elite paramilitary, and the unit was reorganized as the 5th SS-Freiwilligen-Sturmbrigade Wallonien with SS-Hauptstürmfuhrer (Captain) Leon Degrelle as its chief of staff. Elevated to new heights of combat prowess, the 2,000 men of the now fully motorized brigade were rushed to the Ukranian sector of the front in November 1943 to halt the Russian advance. During the bloody engagement, the brigade commander was killed, and it fell to Degrelle to quickly take command of what was left of the shattered unit. Degrelle’s questionable grasp of military strategy was compensated for by his unflinching courage, cool head and hard-won battle experience. At a time when the fate of the Walloons hung by a thread, it was often Degrelle’s qualities as a fighting leader that set the example for his men. Few of his troops would ever forget seeing Degrelle, in agony from a deep wound in his side, continue to personally lead them through fighting so ghastly that it was considered completely beyond the comprehension of anyone who had not lived through it.

Despite the hellish conditions, the Belgians managed to hold back the Russian onslaught. Dragging their wounded with them, they fought alongside German units in a desperate rear-guard action through lethal Russian rocket and artillery fire. However, as Degrelle and the exhausted remnants of the brigade closed on the German lines, they appeared certain to be overtaken and massacred by the pursuing Russians. In a heroic act of self-sacrifice, the 5th SS-Panzerdivision Wiking‘s few remaining panzers suddenly turned back to hold off the Red Army units until the Belgians had reached safety.

The heroic stand came at a heavy cost to the brigade but Degrelle would be promoted to SS-Sturmbannführer (Major) and flown out of Russia to be awarded the Knight’s Cross personally by Hitler for his incredible bravery. As the two men discussed the situation on the front, it was apparent that Hitler not only had a great personal interest in the progress of the brigade but also held Degrelle in high esteem.

In 1944, the brigade found themselves almost encircled in the Baltic, fending off an insurmountable onslaught. For three weeks during the Battle of Narva, Degrelle’s mostly inexperienced Walloons had been committed to heavy combat. Only 32 of the original 300 recruits survived to rejoin the unit. Degrelle was flown out of Estonia and once again brought before Hitler on August 27, 1944. He had the unique distinction of being one of the few non-ethnic Germans to be awarded the coveted Oak Leaves to the Knights Cross along with the prestigious Close Combat Clasp in gold, awarded to men who had fought through more than 50 days of close-quarter combat. During this encounter, Hitler is said to have stated to Degrelle that “If I had a son, I would want him to be like you”.

Despite being virtually annihilated during its service in Russia and Estonia, the Wallonien Brigade was to be upgraded in September 1944 to form the 28th SS-Division, commanded by the now SS-Oberstürmbannfuhrer (Lieutenant Colonel) Leon Degrelle.

In the waning months of the Reich, an offensive in Pomerania was launched with all the customary élan and ferocity typical of the Waffen-SS. Degrelle once again led from the front as his Walloons fought fanatically in the face of overpowering Soviet forces. The offensive soon stalled however, and ultimately accomplished little other than to precipitate a powerful Soviet counteroffensive. They were doggedly forced back through central Pomerania and towards Berlin. By mid-March 1945, following weeks of unrelenting combat in the hopelessly one-sided fight, Degrelle’s division had been burned to a cinder.

As destruction loomed at the gates of the German capital, Degrelle saw ample evidence of the German Army’s total collapse. The stiff, lifeless bodies of countless Wehrmacht and Volkssturm soldiers, suspected of desertion, had been left hanging by the roadside from trees, lamp posts, and makeshift gallows as a gruesome warning to others. In spite of the draconian measures being employed by the SS, Degrelle decided to release those volunteers who no longer wished to fight. They were free to make their way home to Belgium or elsewhere. Others were given foreign worker cards and disguised as conscripted laborers. From the remaining 650 officers and men, he formed one well-equipped battalion to continue the futile struggle. Even though Hitler was dead, the remaining Walloons recognized that as foreign volunteers they had no future beyond the Reich and would be treated as traitors in their homeland despite their unimaginable sacrifice. Their fate was sealed. With the sword of Damocles hanging over their heads, many saw death in combat as the only course open to them, and were determined to fight to the bitter end.

“They died out there, in countless numbers, not for government officials in Berlin, but for their old countries, gilded by the centuries, and for their common fatherland, Europe, the Europe of Virgil and Ronsard, the Europe of Erasmus and Nietzsche, of Raphael and Dürer, the Europe of St. Ignatius and St. Theresa, the Europe of Frederick the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte.” — Leon Degrelle, The Eastern Front: Memoirs of a Waffen SS Volunteer, 1941–1945