Stiklestad

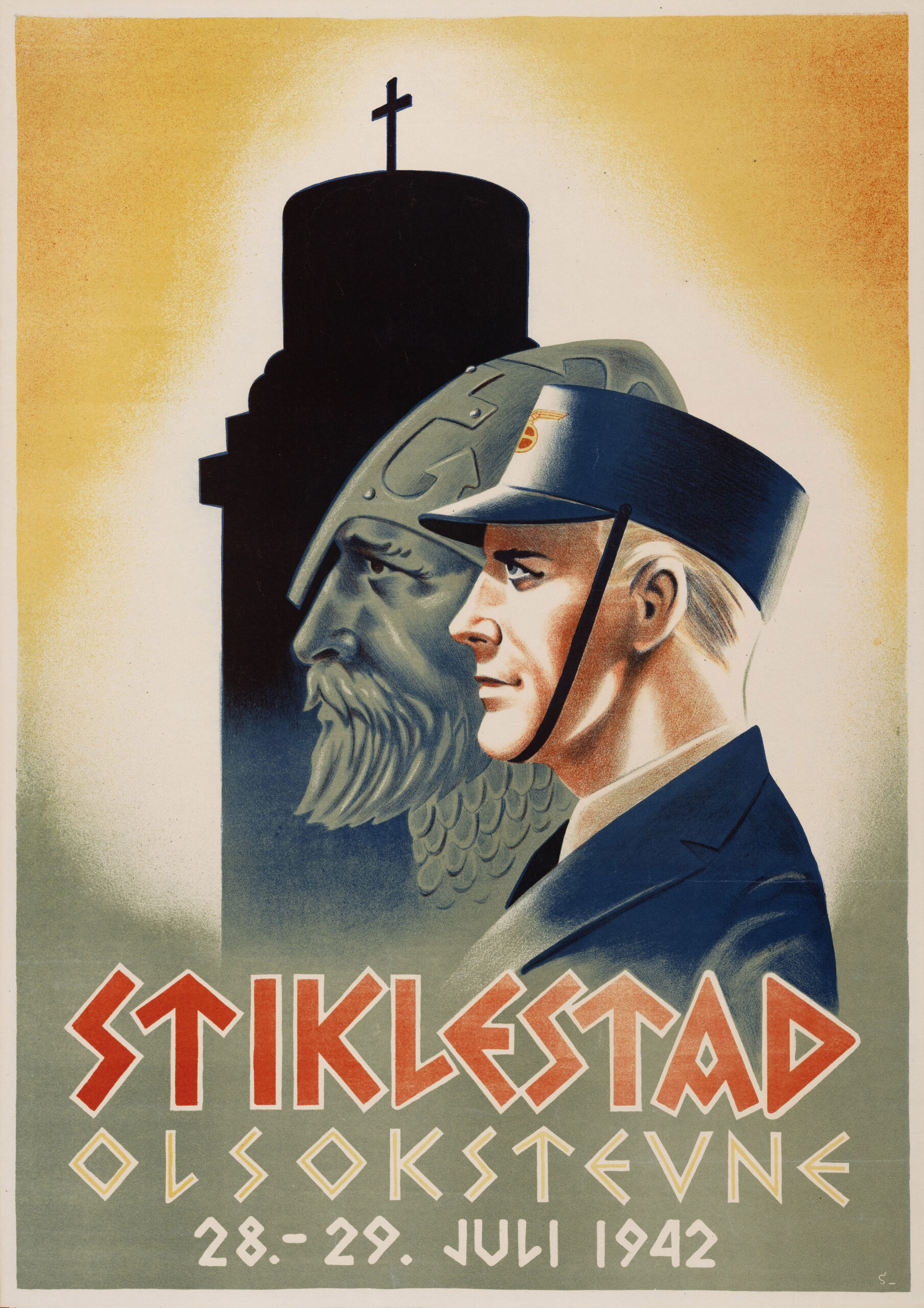

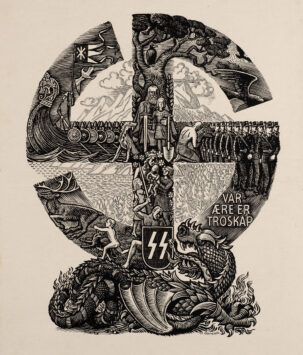

The Battle of Stiklestad in 1030 is considered one of the most famous battles from Norwegian history, holding great significance as part of the country’s national myth. The decisive encounter between Cnut’s pagan forces and Olaf II’s Christian army ended with the latter’s victory and the christianization of Norway. The victory would cost Olaf II his life, but would cement his status as a martyr of the church in the process. Propaganda proclaiming the heroic nature of Saint Olaf’s sacrifice made for valuable nation-building material in the newly christianized Norwegian state, where the warrior ethic of the Vikings and their pagan gods and goddesses were yet held in high regard. To facilitate an ultranationalist rebirth of Norway, the Nasjonal Samling would call upon Olaf’s medieval triumphs once again to kindle feelings of national belongingness.

The issuing body of this poster, the fascist National Samling party, had a strong Christian wing that embraced the party’s rhetoric of the need for a ‘spiritual’ awakening in order to wipe out materialism and the alleged anomie and decadence of modern societies. The party program stated that “the core values of Christianity [must be] defended” and the Nasional Samling used the Cross of St. Olaf as its emblem, a symbol that referred to the aforementioned warrior-king Olaf II who Christianized and unified the country. Within the Nasjonal Samling, this Christian wing sought a movement that would replace divisive parties and class conflict with a gathering of people in a national ‘rassemblement’ on the basis of Christianity. For example Kjeld Stub, who was one of its most notable Christian figures, claimed in 1934 that the National Samling did not represent “ordinary politics, but a new spiritual uprising, both of a religious and national nature”, encapsulating the root essence of this poster.

The poster highlights furthermore an important political tenet within Fascist ideology known as ‘palingenisis’, that draws elements from the past which are incorporated into a contemporary narrative of interconnectedness and meaningfulness, and applied to modern life. A member of the Nasjonal Samling, identifiable by his characteristic kepi, is featured alongside the spirit of an ancestral participant of the battle, legitimizing the Nasjonal Samling and its paramilitary Hirden (named after the medieval Norwegian king’s praetorian guard) as a national institution, also linking its members to a venerable warrior past.

Others such as Vidkun Quisling secured his legitimacy in the eyes of the nation by drawing on myths surrounding the warrior-king St. Olaf and Harald Hårfagre, and wrote that just as Norway was united and Christianized by force his fascist rule was only going to be able to resurrect past greatness through the use of force: “All legitimate means must be used if [our policy] it is to have an effect, and since people, as a rule, only have understanding and respect for power, one has to use power in order to establish the rule of law and a bring about the resurrection of the country. Norway was united by power. And it became Christian by power.”

Free shipping on orders over $50!

- Satisfaction Guaranteed

- No Hassle Refunds

- Secure Payments

The Battle of Stiklestad in 1030 is considered one of the most famous battles from Norwegian history, holding great significance as part of the country’s national myth. The decisive encounter between Cnut’s pagan forces and Olaf II’s Christian army ended with the latter’s victory and the christianization of Norway. The victory would cost Olaf II his life, but would cement his status as a martyr of the church in the process. Propaganda proclaiming the heroic nature of Saint Olaf’s sacrifice made for valuable nation-building material in the newly christianized Norwegian state, where the warrior ethic of the Vikings and their pagan gods and goddesses were yet held in high regard. To facilitate an ultranationalist rebirth of Norway, the Nasjonal Samling would call upon Olaf’s medieval triumphs once again to kindle feelings of national belongingness.

The issuing body of this poster, the fascist National Samling party, had a strong Christian wing that embraced the party’s rhetoric of the need for a ‘spiritual’ awakening in order to wipe out materialism and the alleged anomie and decadence of modern societies. The party program stated that “the core values of Christianity [must be] defended” and the Nasional Samling used the Cross of St. Olaf as its emblem, a symbol that referred to the aforementioned warrior-king Olaf II who Christianized and unified the country. Within the Nasjonal Samling, this Christian wing sought a movement that would replace divisive parties and class conflict with a gathering of people in a national ‘rassemblement’ on the basis of Christianity. For example Kjeld Stub, who was one of its most notable Christian figures, claimed in 1934 that the National Samling did not represent “ordinary politics, but a new spiritual uprising, both of a religious and national nature”, encapsulating the root essence of this poster.

The poster highlights furthermore an important political tenet within Fascist ideology known as ‘palingenisis’, that draws elements from the past which are incorporated into a contemporary narrative of interconnectedness and meaningfulness, and applied to modern life. A member of the Nasjonal Samling, identifiable by his characteristic kepi, is featured alongside the spirit of an ancestral participant of the battle, legitimizing the Nasjonal Samling and its paramilitary Hirden (named after the medieval Norwegian king’s praetorian guard) as a national institution, also linking its members to a venerable warrior past.

Others such as Vidkun Quisling secured his legitimacy in the eyes of the nation by drawing on myths surrounding the warrior-king St. Olaf and Harald Hårfagre, and wrote that just as Norway was united and Christianized by force his fascist rule was only going to be able to resurrect past greatness through the use of force: “All legitimate means must be used if [our policy] it is to have an effect, and since people, as a rule, only have understanding and respect for power, one has to use power in order to establish the rule of law and a bring about the resurrection of the country. Norway was united by power. And it became Christian by power.”