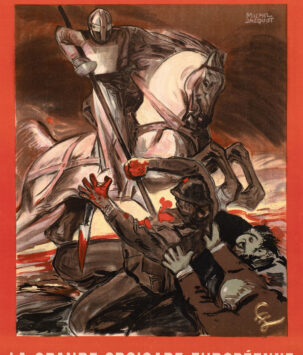

Freedom – Independence

Poster from the Vlaamsch Nationaal Verbond (Flemish National League, VNV), which was a devoutly catholic, Flemish nationalist organization that was founded in Belgium in 1933 by staunchly nationalistic veteran Flemish front-line soldiers of the Great War. Their primary goal was to form an independent Flemish state, having been embittered by the Great War and long oppressed by the French-speaking Walloon minority which dominated the Belgian government. The party rejected the illegitimate Belgian nation-state, and advocated for the unification of Flanders, the Netherlands and other Flemish regions in northern France into a single polity known as Dietsland, otherwise known as the ‘Greater Netherlands’. The symbol of the VNV was a triangle within a circle, with the circle representing the union of the regions and the triangle representing the delta formed by the Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt rivers.

The VNV shared many of its ideological elements with Verdinaso, another third-positionist political movement in pre-war Belgium. The VNV differed from the Verdinaso in several crucial ways however, including not initially being an anti-Semitic organization. This would change with the German occupation beginning in 1940, with which the VNV was forced to cooperate with the National Socialist authorities. The VNV would be offered a leading position in this new collaborationist regime and would take up this mantle. In a speech on October 11th, 1940, co-founder and leader of the VNV, Staf de Clercq, would clarify this stance by proclaiming the following:

“Flanders must join the new order, born of the National Socialist revolution. This order can only be established on the basis of a pure and true popular consciousness, which for the people of Flanders means the awareness of its Dutch character and the sense of Germanic solidarity for which Germanic honor and duty demand.

Therefore, the task of the movement consists of arousing and strengthening popular national consciousness in Flanders, in educating all fellow citizens in a National Socialist spirit, to subordinate personal and group interests to the well-being of the Volksgemeinschaft [people’s community] and in converting this popular alliance into a political, cultural and social economic order.

Healthy political-national construction must be carried out on a national basis. This new political order must be established, partly on the principle of leadership, and partly on the elimination and rejection of all institutions, groups or expressions that affect or undermine the organic unity of the people’s community.

The cultural order must serve the construction of a truly national culture, that is to say, a culture that in all its manifestations is the reflection of national identity. As such, as a means of maintaining and perfecting it, the social order will be based on the recognition of work as a service to the wider community and as the highest duty for all. The solidarity of workers of every kind and of every rank, of leaders and of followers, whose solidarity must be built on mutual respect, loyalty and the duty of the community to ensure a humane existence for all diligent fellow citizens. The economic order will be aimed at the realization of a twofold principle: property is service and the interest of the community takes precedence over the interest of groups and individuals. In recognizing private initiative, the organization of businesses must aim to make the national economy an ordered, bound whole of the entire Volk (people). When everyone understands their duty, our Flemish, Dutch and Germanic resurrection will grow out of the current chaos in the new order.” (Van der Auwera, 2013)

Throughout the occupation, the VNV actively recruited men for the Waffen-SS. The Flemish youth rallied behind the calls of their families and the church to fight for Flanders against the ‘Red’ invasion of Europe. These men would serve in units such as the SS-Freiwilligen-Sturmbrigade Langemarck, with Hitler himself stating of these Flemish soldiers that they “have indeed shown themselves on the Eastern Front to be more pro-German and more ruthless than the Dutch legionaries”. The élan displayed by these volunteers embodied the imagery of their medieval knightly ancestors as featured in this poster, Flemish knights having been considered some of the most effective and well-respected within Europe during the High Middle Ages (Harl, 2023). Upon returning home to their native Flanders after the war however, many of these brave volunteers would be greeted with executions or jailed by the Belgian state. Some would go on to author their memoirs including Remy Schrijnen’s ‘Last Knight of Flanders‘.

Sources:

Van der Auwera, G. (2013). Een merkwaardige rede – toespraak door Staf De Clercq. Traces of War. Retrieved from https://www.tracesofwar.nl/articles/1806/Een-merkwaardige-rede—toespraak-door-Staf-De-Clercq-10-11-1940.htm

Harl, K. W. (2023). Empires of the Steppes: A History of the Nomadic Tribes Who Shaped Civilization. United States: Hanover Square Press. pp. 263, 516.

Free shipping on orders over $50!

- Satisfaction Guaranteed

- No Hassle Refunds

- Secure Payments

Poster from the Vlaamsch Nationaal Verbond (Flemish National League, VNV), which was a devoutly catholic, Flemish nationalist organization that was founded in Belgium in 1933 by staunchly nationalistic veteran Flemish front-line soldiers of the Great War. Their primary goal was to form an independent Flemish state, having been embittered by the Great War and long oppressed by the French-speaking Walloon minority which dominated the Belgian government. The party rejected the illegitimate Belgian nation-state, and advocated for the unification of Flanders, the Netherlands and other Flemish regions in northern France into a single polity known as Dietsland, otherwise known as the ‘Greater Netherlands’. The symbol of the VNV was a triangle within a circle, with the circle representing the union of the regions and the triangle representing the delta formed by the Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt rivers.

The VNV shared many of its ideological elements with Verdinaso, another third-positionist political movement in pre-war Belgium. The VNV differed from the Verdinaso in several crucial ways however, including not initially being an anti-Semitic organization. This would change with the German occupation beginning in 1940, with which the VNV was forced to cooperate with the National Socialist authorities. The VNV would be offered a leading position in this new collaborationist regime and would take up this mantle. In a speech on October 11th, 1940, co-founder and leader of the VNV, Staf de Clercq, would clarify this stance by proclaiming the following:

“Flanders must join the new order, born of the National Socialist revolution. This order can only be established on the basis of a pure and true popular consciousness, which for the people of Flanders means the awareness of its Dutch character and the sense of Germanic solidarity for which Germanic honor and duty demand.

Therefore, the task of the movement consists of arousing and strengthening popular national consciousness in Flanders, in educating all fellow citizens in a National Socialist spirit, to subordinate personal and group interests to the well-being of the Volksgemeinschaft [people’s community] and in converting this popular alliance into a political, cultural and social economic order.

Healthy political-national construction must be carried out on a national basis. This new political order must be established, partly on the principle of leadership, and partly on the elimination and rejection of all institutions, groups or expressions that affect or undermine the organic unity of the people’s community.

The cultural order must serve the construction of a truly national culture, that is to say, a culture that in all its manifestations is the reflection of national identity. As such, as a means of maintaining and perfecting it, the social order will be based on the recognition of work as a service to the wider community and as the highest duty for all. The solidarity of workers of every kind and of every rank, of leaders and of followers, whose solidarity must be built on mutual respect, loyalty and the duty of the community to ensure a humane existence for all diligent fellow citizens. The economic order will be aimed at the realization of a twofold principle: property is service and the interest of the community takes precedence over the interest of groups and individuals. In recognizing private initiative, the organization of businesses must aim to make the national economy an ordered, bound whole of the entire Volk (people). When everyone understands their duty, our Flemish, Dutch and Germanic resurrection will grow out of the current chaos in the new order.” (Van der Auwera, 2013)

Throughout the occupation, the VNV actively recruited men for the Waffen-SS. The Flemish youth rallied behind the calls of their families and the church to fight for Flanders against the ‘Red’ invasion of Europe. These men would serve in units such as the SS-Freiwilligen-Sturmbrigade Langemarck, with Hitler himself stating of these Flemish soldiers that they “have indeed shown themselves on the Eastern Front to be more pro-German and more ruthless than the Dutch legionaries”. The élan displayed by these volunteers embodied the imagery of their medieval knightly ancestors as featured in this poster, Flemish knights having been considered some of the most effective and well-respected within Europe during the High Middle Ages (Harl, 2023). Upon returning home to their native Flanders after the war however, many of these brave volunteers would be greeted with executions or jailed by the Belgian state. Some would go on to author their memoirs including Remy Schrijnen’s ‘Last Knight of Flanders‘.

Sources:

Van der Auwera, G. (2013). Een merkwaardige rede – toespraak door Staf De Clercq. Traces of War. Retrieved from https://www.tracesofwar.nl/articles/1806/Een-merkwaardige-rede—toespraak-door-Staf-De-Clercq-10-11-1940.htm

Harl, K. W. (2023). Empires of the Steppes: A History of the Nomadic Tribes Who Shaped Civilization. United States: Hanover Square Press. pp. 263, 516.