French Legionnaire Grouping

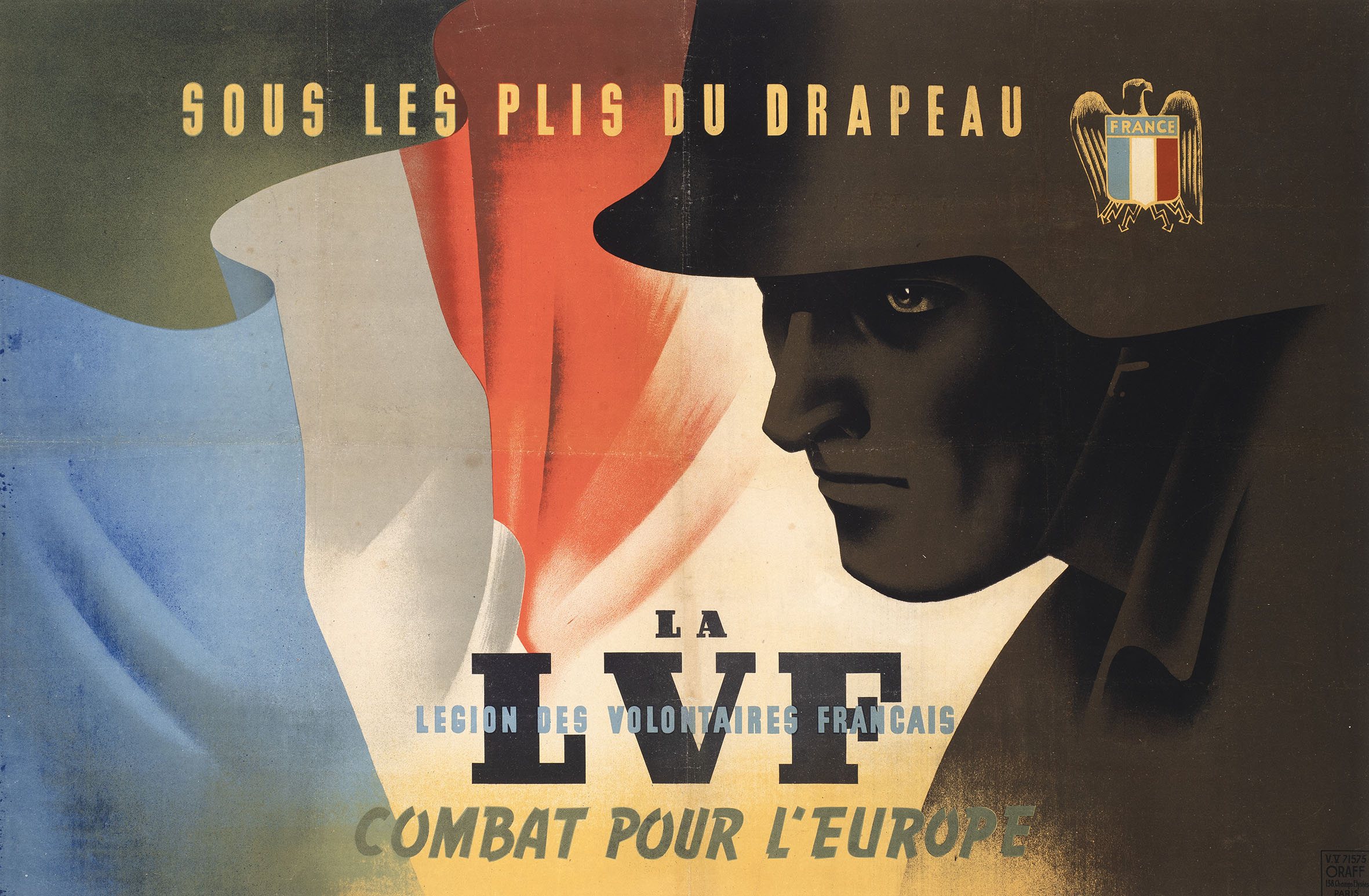

Seen here is a recruitment poster for the Légion des volontaires français (LVF) and a regimental standard of the Légion française des combattants (LFC), both associated with the French collaboration. Despite their shared political affiliations and identification as French legionary organizations, each handled a different function. The LFC was a veteran’s organization that concerned itself with domestic matters, while the LVF was a military unit comprised of Frenchmen who fought alongside the Germans, ostensibly to defend Europe against Bolshevism. It served as the 638th Infantry Regiment within the Wehrmacht and saw heavy frontline combat. It was later redesignated as the Waffen-SS ‘Charlemagne’ Brigade, named after the legendary medieval Frankish King Charlemagne. The LVF originated as an independent initiative by a coalition of far-right factions in Vichy France who were disillusioned with the liberalism of the Third Republic.

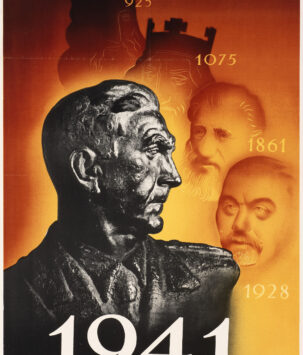

The Legion’s flagpole top seen here is a winged helmet of ancient Gaul, and alongside the unit’s later identification with the legend of Charlemagne, we see the clear and distinct influence of romantic historicism and French national mythology. The Waffen-SS ‘Charlemagne’ Brigade distinguished itself in the Battle of Berlin in 1945, where it remained as one of the last units fending off the insurmountable Soviet onslaught. In a dramatic demonstration of gallantry befitting of their namesake, the members of the Charlemagne Brigade would make a valiant last stand at the Reich Chancellery, where they would destroy 108 Soviet tanks in the process. Indeed, the last defenders in the area of Hitler’s Führerbunker complex were to be these Frenchmen. Eugene Vaulot, a 21-year-old Parisian who volunteered to partake in the defense of Berlin, knocked out 6 Soviet tanks on the 30th of April above the bunker complex where Hitler would take his own life on the very same day. It is indeed a thought-provoking twist of fate that a patriotic band of Frenchmen should willingly serve as Hitler’s last line of defense.

As with the rest of Western Europe, the German occupation of France was stern but lenient compared to that experienced by the Reich’s eastern conquests; the gentile French population were never targeted by the same genocidal machinations that sought to racially cleanse Eastern Europe of Slavs. Often overlooked is the fact that the Allied bombing campaigns were responsible for killing twice as many French civilians as were executed by the German military administration. 68,778 civilians lost their lives due to indiscriminate bombing by Anglo-American forces (Florentin, 1997) as opposed to the 30,000 fatalities caused by the occupying forces (Dear & Foot, 2005, p. 321). Moreover, many French municipalities were obliterated by the same Allied terror bombings, including 96% of Tilly-la-Campagne (Calvados), 95% of Calais (Pas-de-Calais), Vire (Calvados), Royan (Charente-Maritime), 94% of Le Portel (Pas-de-Calais) and 90% of Dunkerque being destroyed, while Saint-Nazaire (Loire Atlantique) was completely flattened (Valla, 2001).

Such brazen double-standards are abounding in Western historiography of the war. The Oradour-sur-Glane massacre, on which dozens of books have been written about what was essentially standard procedure for both Allied and Axis vanguard units that would spearhead offensive military operations, resulted in 643 deaths. Meanwhile, the 10,00 civilians killed just three days prior by the Allied bombing of Caen receives close to no attention in popular literature.

Sources:

Dear, Ian & Foot, Michael Richard Daniell. (2005). The Oxford Companion to World War II.

Florentin, Eddy. (1997). Quand les Alliés bombardaient la France.

Valla, Jean-Claude. (2001). La France sous les bombes américaines 1942-1945.

Free shipping on orders over $50!

- Satisfaction Guaranteed

- No Hassle Refunds

- Secure Payments

Seen here is a recruitment poster for the Légion des volontaires français (LVF) and a regimental standard of the Légion française des combattants (LFC), both associated with the French collaboration. Despite their shared political affiliations and identification as French legionary organizations, each handled a different function. The LFC was a veteran’s organization that concerned itself with domestic matters, while the LVF was a military unit comprised of Frenchmen who fought alongside the Germans, ostensibly to defend Europe against Bolshevism. It served as the 638th Infantry Regiment within the Wehrmacht and saw heavy frontline combat. It was later redesignated as the Waffen-SS ‘Charlemagne’ Brigade, named after the legendary medieval Frankish King Charlemagne. The LVF originated as an independent initiative by a coalition of far-right factions in Vichy France who were disillusioned with the liberalism of the Third Republic.

The Legion’s flagpole top seen here is a winged helmet of ancient Gaul, and alongside the unit’s later identification with the legend of Charlemagne, we see the clear and distinct influence of romantic historicism and French national mythology. The Waffen-SS ‘Charlemagne’ Brigade distinguished itself in the Battle of Berlin in 1945, where it remained as one of the last units fending off the insurmountable Soviet onslaught. In a dramatic demonstration of gallantry befitting of their namesake, the members of the Charlemagne Brigade would make a valiant last stand at the Reich Chancellery, where they would destroy 108 Soviet tanks in the process. Indeed, the last defenders in the area of Hitler’s Führerbunker complex were to be these Frenchmen. Eugene Vaulot, a 21-year-old Parisian who volunteered to partake in the defense of Berlin, knocked out 6 Soviet tanks on the 30th of April above the bunker complex where Hitler would take his own life on the very same day. It is indeed a thought-provoking twist of fate that a patriotic band of Frenchmen should willingly serve as Hitler’s last line of defense.

As with the rest of Western Europe, the German occupation of France was stern but lenient compared to that experienced by the Reich’s eastern conquests; the gentile French population were never targeted by the same genocidal machinations that sought to racially cleanse Eastern Europe of Slavs. Often overlooked is the fact that the Allied bombing campaigns were responsible for killing twice as many French civilians as were executed by the German military administration. 68,778 civilians lost their lives due to indiscriminate bombing by Anglo-American forces (Florentin, 1997) as opposed to the 30,000 fatalities caused by the occupying forces (Dear & Foot, 2005, p. 321). Moreover, many French municipalities were obliterated by the same Allied terror bombings, including 96% of Tilly-la-Campagne (Calvados), 95% of Calais (Pas-de-Calais), Vire (Calvados), Royan (Charente-Maritime), 94% of Le Portel (Pas-de-Calais) and 90% of Dunkerque being destroyed, while Saint-Nazaire (Loire Atlantique) was completely flattened (Valla, 2001).

Such brazen double-standards are abounding in Western historiography of the war. The Oradour-sur-Glane massacre, on which dozens of books have been written about what was essentially standard procedure for both Allied and Axis vanguard units that would spearhead offensive military operations, resulted in 643 deaths. Meanwhile, the 10,00 civilians killed just three days prior by the Allied bombing of Caen receives close to no attention in popular literature.

Sources:

Dear, Ian & Foot, Michael Richard Daniell. (2005). The Oxford Companion to World War II.

Florentin, Eddy. (1997). Quand les Alliés bombardaient la France.

Valla, Jean-Claude. (2001). La France sous les bombes américaines 1942-1945.