Resurgent Netherlands

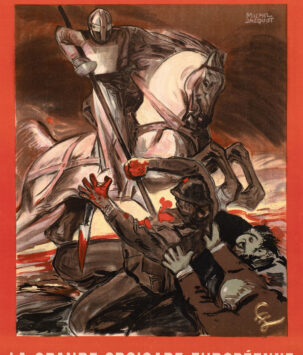

Dutch poster from the German occupation promoting an exhibition about the economic and cultural revival of the Netherlands. A Wolfsangel, symbol of the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (NSB) otherwise known the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands, is displayed prominently in the middle. A sword and spade, symbolizing the dual pillars of National Socialism, surmount the Wolfsangel, with the sword representing the iron will of the ‘nation’ and its Volk, while the spade does the ‘social’ commitment of labor as a national duty in the pursuit of economic autarky and for the greater good of the Volk.

Contrary to popular belief, the Dutch territories experienced a significant economic boom under the new National Socialist administration which began in 1940. New calculations of macroeconomic statistics for the period 1938 to 1948 show that that the first year and a half of the German occupation coincided with the best economic performance of the decade, according to Professor Ham Klemann of Erasmus University. His studies further conclude that not only was industrial capacity in 1945 larger than in 1940, the Dutch population actually grew during this period. Reichskommissar Arthur Seyss-Inquart’s first objective was to resolve unemployment, and stated during the Nuremberg trials that his “conscience was untroubled” as he improved the conditions of the Dutch people while serving them.

Here is yet another anecdote from history which is seldom given any recognition due to its incongruence with mainstream narratives about the war, of which there are many. In the immediate post-war period, private and public institutions across Europe had good reason to draw attention to losses and to conceal any profitable business that had occurred during the war. Western European governments selectively portrayed to the outside world a destroyed country, a ruined economy and starving masses in the hopes of garnering compassion alongside American aid and German compensation. The Dutch Minister of Economic Affairs at the time prohibited the publication of the aforementioned macroeconomic data, as they would potentially undermine his position in the ongoing negotiations for American aid to be received through the Marshall Plan. Similarly, when the Allied press released images of healthy Dutch women celebrating VE day with American and British troops, the Hague made sure to disseminate photographs of starving children and the elderly in the most miserable circumstances to garner further sympathy and additional economic aid.

Text reads (from left to right, top to bottom): 29th of August – 27th of September. Exhibition. Selection from the Schuilenberg Collection. Resurgent Netherlands. [Address] Free Entry. Utrecht. [Opening times]

Free shipping on orders over $50!

- Satisfaction Guaranteed

- No Hassle Refunds

- Secure Payments

Dutch poster from the German occupation promoting an exhibition about the economic and cultural revival of the Netherlands. A Wolfsangel, symbol of the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (NSB) otherwise known the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands, is displayed prominently in the middle. A sword and spade, symbolizing the dual pillars of National Socialism, surmount the Wolfsangel, with the sword representing the iron will of the ‘nation’ and its Volk, while the spade does the ‘social’ commitment of labor as a national duty in the pursuit of economic autarky and for the greater good of the Volk.

Contrary to popular belief, the Dutch territories experienced a significant economic boom under the new National Socialist administration which began in 1940. New calculations of macroeconomic statistics for the period 1938 to 1948 show that that the first year and a half of the German occupation coincided with the best economic performance of the decade, according to Professor Ham Klemann of Erasmus University. His studies further conclude that not only was industrial capacity in 1945 larger than in 1940, the Dutch population actually grew during this period. Reichskommissar Arthur Seyss-Inquart’s first objective was to resolve unemployment, and stated during the Nuremberg trials that his “conscience was untroubled” as he improved the conditions of the Dutch people while serving them.

Here is yet another anecdote from history which is seldom given any recognition due to its incongruence with mainstream narratives about the war, of which there are many. In the immediate post-war period, private and public institutions across Europe had good reason to draw attention to losses and to conceal any profitable business that had occurred during the war. Western European governments selectively portrayed to the outside world a destroyed country, a ruined economy and starving masses in the hopes of garnering compassion alongside American aid and German compensation. The Dutch Minister of Economic Affairs at the time prohibited the publication of the aforementioned macroeconomic data, as they would potentially undermine his position in the ongoing negotiations for American aid to be received through the Marshall Plan. Similarly, when the Allied press released images of healthy Dutch women celebrating VE day with American and British troops, the Hague made sure to disseminate photographs of starving children and the elderly in the most miserable circumstances to garner further sympathy and additional economic aid.

Text reads (from left to right, top to bottom): 29th of August – 27th of September. Exhibition. Selection from the Schuilenberg Collection. Resurgent Netherlands. [Address] Free Entry. Utrecht. [Opening times]